Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta CEO: Heading into 2025 with Positive Economic Outlook, Mindful of Risks

Wednesday, December 4th, 2024

Key Points

-

Conditions on both sides of the Fed's mandate appear to be broadly healthy, and Bostic's economic outlook is positive. He explains uncertainties still persist, however, and risks loom for price stability and the labor market.

-

Atlanta Fed researchers are trying to determine whether the labor market may be cooling more dramatically than Bostic had imagined when he developed his outlook for the economy.

-

While inflation readings have experienced bumpiness, Bostic doesn't think progress toward price stability has completely stalled.

-

A major factor contributing to the continued stubbornness of elevated inflation has been housing prices. Market-based measures of rental price growth have been much more muted than the official inflation statistics, Bostic says, and that softening in market rents should eventually filter through to the statistics.

-

Bostic also is not seeing signs that a surge in economic energy that could spark inflationary pressures is imminent. He explains inflation expectations have remained quite stable and relatively in line with prepandemic norms.

-

Regarding the path ahead for monetary policy, Bostic says his strategy will be to look to the incoming data, information from the Atlanta Fed's portfolio of surveys, the balance of risks, and input from the Bank's business contacts.

At its November meeting, the Federal Open Market Committee reduced the target for its benchmark interest rate, the federal funds rate, by a quarter percentage point—to a range of 4-1/2 to 4-3/4 percent. That came after we lowered the policy rate by a half percentage point in September, so it has come down three-quarters of a percentage point, or 75 basis points, from its high.

I voted for both moves because I believe inflation remains on a path, albeit a bumpy one, toward the Committee's objective of 2 percent, per the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. The risks to achieving the Committee's dual mandates of maximum employment and price stability have shifted such that they are roughly in balance, so we likewise should begin shifting monetary policy toward a stance that neither stimulates nor restrains economic activity.

Conditions on both sides of the Fed's mandate—price stability and maximum employment—appear to be broadly healthy. Nevertheless, a continuation of the positive string of macroeconomic developments is not assured. Uncertainties persist on various fronts and risks loom both for the health of the labor market and price stability. As always, I am paying close attention to all the risks and uncertainties.

Which way forward for labor markets?

Let's start with the labor market. From a big-picture perspective, the labor market is cooling from a red-hot state in which demand for workers far exceeded supply for multiple years. Through October 2024, monthly payroll growth has averaged 170,000 jobs this year, lower than the three previous years of blockbuster job gains, yet still stronger than the last prepandemic year of 2019 (chart 1).

The salient question for me today is whether the labor market is cooling more dramatically than I had imagined when I developed my outlook for the economy. The answer has important implications for monetary policy, because if conditions in the labor market are in fact worse than my Committee colleagues and I thought a few months ago, then that probably bolsters the case for continuing to remove policy restrictiveness, and perhaps argues that we should do so more aggressively.

Our research team here in Atlanta is exploring this question from various angles.

For one, we are looking at a trend that could potentially exacerbate any existing labor market weakness. Economists Tao Zha and Jon Willis have noted that the difference between the number of net jobs created from new businesses opening and the number of jobs lost from businesses closing has declined recently. This has occurred during a time when the burst of new-business formation we observed coming out of the pandemic has dissipated. Taken together, it is clear that a key jobs generator has lost strength, which implies labor markets may weaken more sharply in coming quarters.

Furthermore, during much of 2022 and 2023 when the Fed was tightening monetary policy, there were far more job openings than workers to fill them. This suggested that a cooling labor market could help reduce inflation without threatening a damaging spike in unemployment, because these so-called "excess vacancies" would need to be eliminated before actual employed people would be laid off.

Excess vacancies have, indeed, fallen steadily since peaking in early 2022 and our economists argue that we may be nearing a point where further declines in job openings could make it considerably harder for workers to find employment. In other words, further slowing in the labor market, measured by the ratio of unemployment-to-job vacancies, could mean higher future unemployment without a payoff in the form of a big downward push on inflation.

By contrast, a different look at job openings suggests the labor market could be in a less precarious state. Economist David Wiczer has been exploring a concept called vacancy yield—that is, the rate at which a job opening gets filled. Using data on job openings, as reported in the US Bureau of Labor Statistics' Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, he shows that the vacancy yield has declined substantially since the pandemic.

We don't fully understand why job openings are translating to fewer hires than before. It could be that firms are more frequently posting vacancies they don't truly plan to fill. Or perhaps the existence of a smaller pool of available workers has allowed them to be more selective, which may prolong the hiring process. If filling an opening takes two months instead of one, to use a simple example, then the opening remains in the data twice as long, and we measure twice as many vacancies in a given month even though firms' desired hires are not twice as high.

Regardless of why this is happening, lower vacancy yields potentially put a different spin on the record levels of job openings observed in 2022 and 2023. Instead of the high number of openings reflecting increased demand by employers, which has been conventional wisdom in many circles, it could be that the elevated openings were a recognition by employers that they needed to post more jobs to yield the same number of workers. If so, then labor markets may not have been as tight as one might have believed, and the inflationary pressures coming from labor markets may not have been as acute one may have believed. The takeaway: policy might need to do less than originally thought.

I see a couple of implications from this research. First, the falling number of job vacancies would seem to validate that monetary policy has been truly restrictive. At the same time, none of these trends send a strong signal that the labor market is rapidly deteriorating nor extremely tight. Instead, they suggest that the labor market is cooling in a largely orderly fashion in the face of higher interest rates, a perspective we also hear from our business contacts. This is welcome news. That said, an important question remains: Just how strong is the labor market? I will be working with my team to gain greater clarity on this moving forward.

The path to 2 percent inflation, while bumpy, looks sustainable

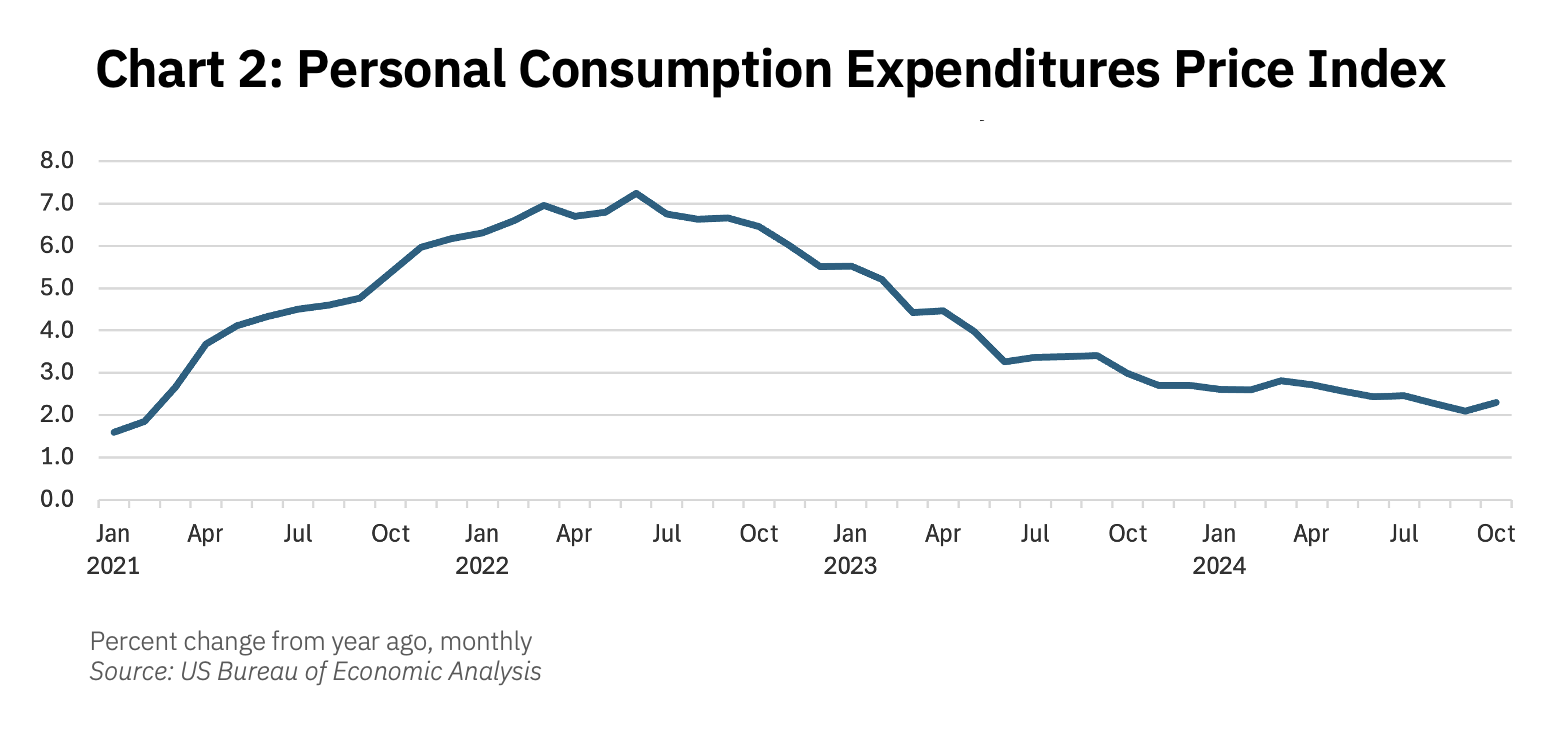

So, what about price stability? The downward trajectory of inflation has been bumpy of late. Looking at the PCE index, the overall year-over-year inflation rate has gradually declined over the past six months, but not in a rapid, straight-line fashion (chart 2). The "core rate" that excludes more volatile food and energy prices has stubbornly hovered around 2.6–2.7 percent.

There are certainly upside risks to price stability. Indeed, our Underlying Inflation Dashboard shows that many measures of inflation remain well above target. Still, weighing the totality of the data, I do not view the recent bumpiness as a sign that progress toward price stability has completely stalled.

Why not? There are several reasons.

For one, a major factor contributing to the continued stubbornness of elevated inflation has been housing prices.1 If one excludes the influence of shelter prices on the core consumer price index (CPI) figure for October, for instance, underlying inflation rose at 2.3 percent at an annual rate, far more quiescent than the 3.3 percent reading when housing is included. If one excludes the volatile energy and food prices in addition to shelter prices from calculations, the CPI has risen by just 2 percent.2

The main reason I am not alarmed by the relative strength of shelter prices is that pure market-based measures of rental price growth from services like Zillow or CoreLogic have been much more muted than what has been calculated in the CPI and PCE. The softening in market rents over the past year to 18 months should eventually filter through to the official inflation statistics and lead to lower readings.

A second reason why I remain confident that inflation will continue its movement toward 2 percent is that I'm not seeing signs that a surge in economic energy, which could spark inflationary pressures, is imminent. Economic growth has been stronger than expected in recent quarters, yes. But the data and our contacts tell us that economic growth, like the labor market, is cooling, and I expect that to continue.

Along similar lines, aggregate savings rates are lower, as are bank balances for many families. In short, the fuel that could reignite economic activity and inflation seems to be drying up.

A fourth source of comfort lies in measures of inflation expectations, which many economists view as one of the most important factors influencing spending and investment decisions. These measures, some of which we produce via our surveys, have remained quite stable and more or less in line with prepandemic norms.

Finally, information collected from our board members, advisory councils, and grassroots network of business and community contacts reinforces this message. Overall, contacts tell us operating costs continue to stabilize and pricing power continues to diminish.

To be sure, I'm mindful of inflationary risks. Elevated inflation does exist for some services in addition to housing. Despite the conclusion of a tense presidential election, geopolitical uncertainties linger at home and abroad, and could generate renewed inflationary pressures. Given the many twists and turns of the past few years, we need to be on alert for whatever surprises emerge.

That said, my base case on inflation remains that we are on track to reach the 2 percent objective, and I will do whatever it takes to make sure we get there.

Much to untangle as we enter a new year

Looking back on 2024, it has definitely been an eventful economic year. Bumpy data early in the year made it hard to know what was really going on regarding the path of inflation. Consumers remained remarkably resilient. The recalibration of monetary policy commenced in response to the rebalancing of inflation and employment risks. Locally, hurricanes Helene and Milton devastated communities in and near the Atlanta Fed's District and resulted in the most storm-related deaths since Hurricane Katrina. It will take some communities years to recover, if ever.

Through the final weeks of this year and into 2025, the various signals and questions I've highlighted here make clear that monetary policymakers have a great deal to ponder.

A few core questions frame my policy thinking. How restrictive is monetary policy? How restrictive does it need to be to keep inflation declining toward 2 percent? On the flip side, how quickly and by how much do we need to lower the federal funds rate to ensure we don't seriously damage labor markets and inflict undue pain on the American people? The research I've described in this message, along with other research my team is producing, will help me answer these questions as well as others that may arise.

Still, broadly speaking, I judge the economy to be on solid footing. The labor market appears stable at or around maximum employment. And we are nearing price stability.

Though my baseline outlook is positive, we cannot afford to be sanguine. The path ahead for monetary policy is not preset. In making judgments about what this path should look like, my strategy will be to look to the incoming data, information from our portfolio of surveys, the balance of risks, and input from our business contacts. Much hard work lies before us. We stand ready.