Mercer Law Celebrates 150 years of Preparing Practice-ready Lawyers

Thursday, October 5th, 2023

Mercer Law School over its 150-year history has made an indelible mark on Georgia and legal education. It was one of the first law schools to be established in the South — just two years after Mercer University moved to Macon from Penfield in 1871.

Today, there are Mercer Law alumni in all 50 states and many other countries around the globe. Virtually every town and city in Georgia has a Mercer attorney or judge, manifesting the School’s 150-year reputation of preparing practice-ready lawyers, community leaders and public servants.

The Law School started with seven students and the three part-time professors who had won approval from Mercer’s trustees to start a law school. The founders and early faculty were models of lawyers’ involvement and leadership in the larger community.

“The school was conceived in professionalism and dedicated to excellence,” wrote federal judge William Augustus Bootle, LAW ’25, in a history of the Law School in 1990. “These men taught at night after the day’s work was done.”

Today that focus on skillful legal practice has taken Mercer to the 2023 national championship in moot court (appellate advocacy) and a narrow loss to UCLA in the 2023 national trial competition. Overall, Mercer is ranked fourth in the nation in National Trial Advocacy, behind UCLA but still ahead of Harvard.

“For 150 years the Law School has really focused on preparing students for practice and has not lost sight of that, even as we have grown and changed,” said Dean Karen J. Sneddon as she prepared for the school’s celebration of 150 years on Oct. 13.

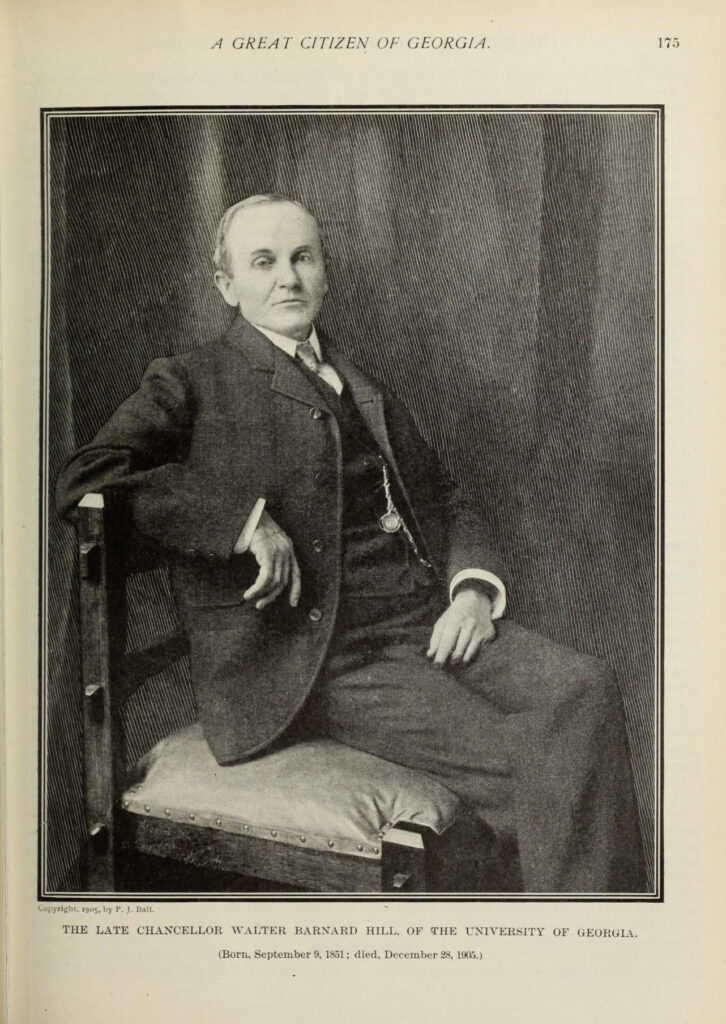

The Law School was the idea of an impressive young lawyer from Talbotton who had finished the University of Georgia Law School in 1871 and joined his father’s law practice in Macon. Walter B. Hill’s first accomplishment had been to create the first Annotated Code of Georgia laws, a model for the nation.

In 1873, Hill concluded that the southern half of Georgia needed a law school. He enlisted Superior Court Judge C.B. Cole and Clifford Anderson, a city alderman who had helped engineer Macon’s successful bid to lure Mercer University from Penfield two years earlier. They won the Mercer trustees’ approval. Judge Cole became chairman of the faculty but died a year later, and Anderson became faculty chairman.

Hill and Anderson would later lead the founding of the Georgia Bar Association, with headquarters in Macon, and serve as early presidents. Anderson became Georgia attorney general in 1880 and served 10 years. The law firm he helped build, now known as Anderson, Walker & Reichert, remains Macon’s oldest law firm. Hill became chancellor of the University of Georgia in 1899.

There was no building, not even a classroom at first. Classes were held in Judge Cole’s courthouse office or in faculty homes. Teaching consisted of lectures and treatises. These more intimate classes further established the faculty as examples of what a Mercer lawyer should be.

In 1875, the Georgia General Assembly authorized Mercer Law School to grant law degrees, which at the time allowed admission to the bar without an exam.

Law schools were proliferating across America then, in part because of the spirt of entrepreneurship in what Mark Twain called the Gilded Age, and in part because the rise of federal laws, railroads, stock exchanges and growing businesses created a demand for lawyers with greater skill and knowledge.

Mercer’s early law graduates gained stature not only in law but in politics, government and other fields. The graduating class in 1876 included William S. West, who became a state senator who led the creation of what is now Valdosta State University and in 1914 became a U.S. senator. Harry Stillwell Edwards, an 1877 graduate, became editor of the Macon Telegraph and a novelist.

The founding faculty took on prominent roles in Georgia. In 1883, Hill and Anderson joined with Macon lawyer Lewis N. Whittle and eight others to establish the Georgia Bar Association. Anderson was the fourth president and Hill, the fifth. Macon was the Georgia Bar’s headquarters for 90 years. One of the early goals of the Georgia Bar was to set higher standards for admission to the bar — standards that would motivate aspiring lawyers to attend law school.

Today, the immediate past president and the president-elect of the bar are Mercer Law graduates Sarah B. “Sally” Akins of Savannah, LAW ’90, and Ivy N. Cadle of Macon, LAW ’07.

In 1886, the new federal judge in Macon, Emory Speer, took on the additional role as dean of the Law School. By 1893, the graduating class had 11 members. Judge William H. Felton, who lived in what is now the Hay House down the hill from the Law School’s current home and whose classes were held in the ground level of the house, joined the faculty in 1899. Clem P. Steed taught in the basement of what is now Mercer’s Godsey Administration Building.

The school continued to attract high-caliber students.

Walter F. George graduated in the Class of 1901 and went into law practice in Cordele and won judgeships on the Superior Court, the Court of Appeals, and finally the Georgia Supreme Court before winning election to the U.S. Senate in 1922. He served for 44 years, chaired the Foreign Relations Committee during World War II and at other times the Finance Committee, which put him in a key position to protect Georgia’s business interests, and became the president pro tem, third in line of succession to the American presidency.

Carl Vinson was in the Class of 1902. He became a powerful senior member of Congress and the only Mercer graduate with a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier bearing his name.

Another student in that class was R.C. Bell. As chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, Bell would be the speaker at the dedication of the Ryals Law Building, the law school’s first real home, in 1930 — just as the current chief justice, Michael P. Boggs, LAW ’90, is to be the speaker at the Law School’s 150th anniversary event in October.

By 1910, the last year with a one-year curriculum, there were 53 students in the graduating class.

In 1917, Mercer opened its Law School to women. That fall, Kathryne Pierce Jackson, known in the style of the day as Mrs. W.E. Jackson, enrolled. The Macon News described her as a teacher and “daughter of Sergeant Patrick Pierce of the police force.” Her husband was reported to work for the fire department. She became president of her senior Law School class. A week after graduation in 1919, she was co-counsel for one of three defendants in the mugging of a doctor on Orange Street and won the case. Three weeks later she became the first woman admitted to practice in Macon’s federal court.

Two more women enrolled that fall. It would be another 45 years, though, before the Law School had its first woman on the faculty: Leah Farb Chanin, a 1954 graduate, hired by the Law School’s longest-serving full-time dean, James P. Quarles (1954-69), to be law librarian and a professor. She served as interim dean 1986-87, the first woman in that role.

In 1920, the Law School got its first home, a makeshift repurposing of the dining room at Sherwood Hall on the Mercer campus. There was “only a partition separating the law library from the University laundry,” wrote Judge Bootle, who became a Mercer Life Trustee and the judge who ordered the integration of the University of Georgia in 1961.

Bigger changes were in store as the Roaring ’20s boosted the nation’s economy. The faculty was now largely full-time. The curriculum expanded to three years. In 1923, Rufus C. Harris, Mercer’s future president, joined the law faculty and led Mercer’s acceptance into the American Association of Law Schools that year and accreditation in 1925 by the American Bar Association. Harris also led the shift from lectures and texts into the discussions of case law.

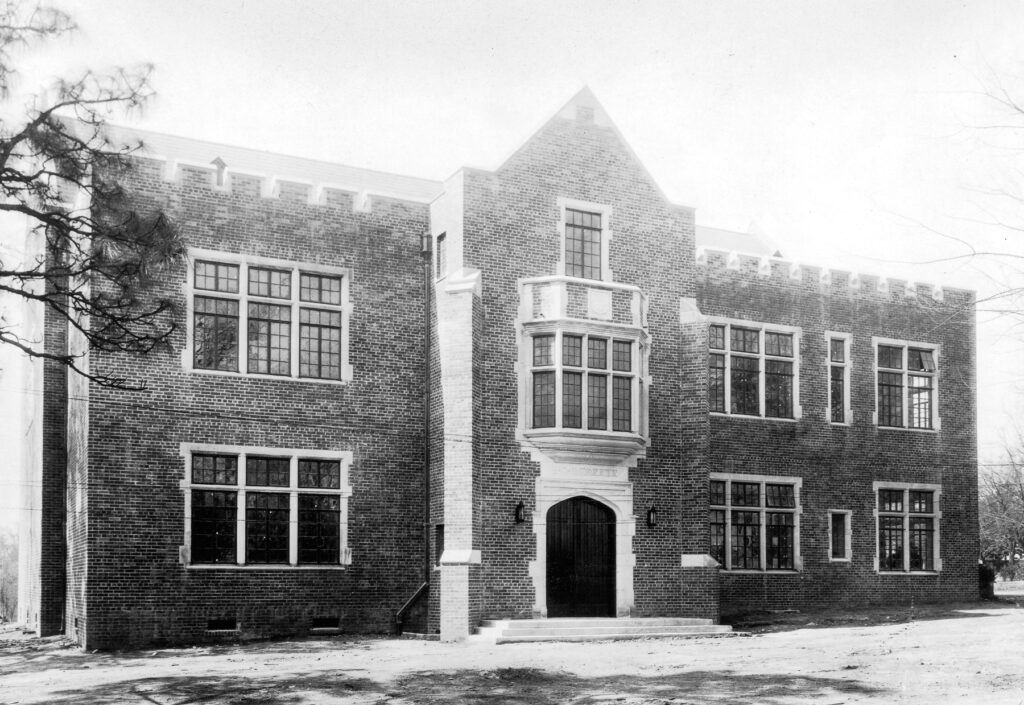

In 1927, Mercer trustee Thomas E. Ryals, a partner in the Anderson law firm, offered to provide a fourth of the cost of a new building for the Law School if others would contribute the rest. More than 400 donors came forward. On June 2, 1930, Ryals Hall was dedicated with space for 125 students. It was the Law School’s first real home and housed the School for the next 48 years.

The Depression of the 1930s hit hard. Enrollment dropped to 45 for the fall of 1932. Judge Bootle, who had been U.S. Attorney in Macon under President Herbert Hoover, became part-time dean — all the School could afford.

After closing during World War II, the school reopened in 1945 with eight students. One was Griffin B. Bell from Americus, who had served in the Army’s Quartermaster Corp. Another was G. Harrold Carswell from Irwinton, who had entered the Navy in 1941. Bell went on to be a federal appellate judge and then attorney general of the United States and chairman of Mercer’s Board of Trustees. Carswell, who likewise became a federal appellate judge, was nominated by President Richard Nixon for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1969, but his nomination was rejected by the U.S. Senate.

On April 8, 1947, Mercer trustees renamed the school the Walter F. George School of Law. The Walter F. George Foundation was created with its own self-perpetuating board, and more than half-a-million dollars promptly poured in to honor George and support the School.

Also in 1947, F. Hodge O’Neal arrived as dean. In the spring of 1948, he announced that, for the first time, “the Law School finds itself unable to admit all who desire to enter.” He capped enrollment at 150 students. He also launched the state’s first law review.

The Law School was 75 years old.

The 1950s and ’60s brought new growth and more change to the Law School. The three-story addition, named for Valdosta businessman Harley Langdale, LAW 1912, housed a new library, a student lounge and faculty offices.

A ceremony in Willingham Chapel on Nov. 16, 1973, jointly celebrated the 100th birthday of the Law School and the 90th birthday of 1902 graduate Carl Vinson, who had retired after 51 years as the U.S. Congressman from Middle Georgia — holding the seat longer than any past member of Congress. President Nixon headlined the event.

Of more enduring significance was the arrival of the first Black students. Mercer President Harris had led the racial integration of the University in 1963, but it was 1969 before the first Black law student, Jerry Boykin, enrolled. The next class brought two more Black students, including the first Black woman, Mary Alice Buckner, LAW ’73, followed by future Mercer trustee and federal judge W. Louis Sands, LAW ’74.

Mercer trustees had also started planning for a new “law center” that could increase the size of the school to 450 students. The ideal building was at the top of beautiful Coleman Hill: a stately four-story building with a clock tower, built in 1954-55 by the Insurance Company of North America to evoke Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. It had replaced a grand mansion that had been atop the hill for 60 years.

The price of the INA building seemed well beyond Mercer’s means, but it was made possible by a deal structure called a “bargain-sale,” in which Mercer would pay in cash the value on INA’s books and the remaining market value would be a charitable gift to Mercer with a tax deduction.

George Woodruff stepped in to provide Mercer’s $1 million cash portion of the deal. Woodruff was the brother of Coca-Cola CEO Robert Woodruff and an entrepreneur in his own right. Woodruff had been a trustee of the Walter F. George Foundation since 1965. More money poured in from other major donors for the interior of the new building. The move-in happened after fall semester of 1977. The formal dedication on May 4, 1979, featured a speech by U.S. Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, introduced by Judge Bell.

The growth that followed brought new challenges, particularly to continue the distinctiveness of a smaller, practice-focused Law School that had attracted students for 100 years. Financing came, one last time, from George Woodruff. At his death at age 91 on Feb. 4, 1987, Woodruff bequeathed to the school Coca-Cola stock, which by 1990 had grown to more than $18 million.

A new dean, Philip D. Shelton, viewed the Woodruff bequest as an opportunity to reposition Mercer in the competitive landscape of law schools. To better compete for the best students, Shelton wanted to reshape the curriculum to emphasize what Mercer had always been known for: producing young lawyers with courtroom skills. The faculty restructured the course of study and created what is still known as the “Woodruff Curriculum.” Legal writing moved to a central place. “Professionalism” was added later to emphasize integrity and community service.

Mercer would now be presented as a law school with a distinctive building, curriculum and culture.

Daisy Hurst Floyd arrived as dean in 2004. She was the first female to be appointed dean through a search process. Her research and teaching had focused on new concepts in legal education, including more clinical experiences for students.

In recent years, more than half of the Law School’s student enrollment has been women. Marilyn Sutton, assistant dean for admissions, said female applicants express particular interest in social justice and making a difference as leaders in their communities. Minority students make up 22% of the enrollment, twice the level from the 1990s, and include Asian and Hispanic as well as Black students. The enrollment target has held at 380 for 30 years.

Sneddon earlier this year was appointed dean, the fourth woman (including Chanin as interim dean) to serve in that capacity.

“When I go and talk with alumni, I am always amazed at how many boards they are on, what kind of leadership positions they may have,” she said.

She talks about the School’s new commitment to civics education in Macon’s public schools and other community service projects and reflects on the careers of prominent graduates over the years.

“I think they were attracted to the Law School because of that connection to service,” Sneddon said. “Our graduates do all kinds of things, but wherever they go, they make a difference.”